Molochio, Reggio di Calabria |

Click Home to go to the main page, or click for an Alphabetic List of all Names. |

Molochio, an area of 37.3 sq km, is a commune (municipality) in the Province of Reggio Calabria in the Italian region Calabria, located about 40 km northeast of the municipality of Reggio Calabria, about an hour's drive away. Molochio is a small farming village in the Aspromonte National Park, surrounded by olive trees, hills and mountains. It ranges from 151 to 310 meters above sea level as referenced to the Marro river. The trees at the higher altitudes are the larch pine, beech and silver fir, maple, and oak. Among these trees you can spot the squirrel, wolf, fox and wild boar. Nearby in the Barva river, immersed in lush vegetation including rare species of ferns, are the waterfalls. Molochio (Greek: Molòcha) is a garden or place of mallows as indicated by the same Greek word (Molochion).

The inhabitants are called Molochiesi and there are about 1,000 families in 1,600 homes. As of December 31, 2004, it had a population of 2,700 which has been steadily decreasing over the years. The town is now divided into three areas: the old town where there are the remains of interesting noble palaces with beautiful granite portals; the area that developed between the two World Wars; and the modern town. The inhabitants are called Molochiesi and there are about 1,000 families in 1,600 homes. As of December 31, 2004, it had a population of 2,700 which has been steadily decreasing over the years. The town is now divided into three areas: the old town where there are the remains of interesting noble palaces with beautiful granite portals; the area that developed between the two World Wars; and the modern town.

The economy of Molochio is based on agriculture and especially on the production of citrus and olives. The agriculture of this area is quite developed to the point of making it one of the richest in the province. The forests of Aspromonte provide the excellent wood for the craftsmen that use it in construction of fixtures, furniture and flooring and which gave birth to many thriving industries for the manufacture of wood and coal production. There is also an oil-processing industry. In the past, they were involved in breeding silkworms. The white mulberry and dark delgelso are still present among the olive groves. The silk industry thrived here until 1800 and while the women waited for the pruned silkworm sang verses of poetry which drew on the legends of chivalry and the death of Orlando. |

This small town's historical records date back to the years 1275 - 1279 when the Abbey of Santa Maria de Merula of Molochio is believed to have been built here, but the precise location has never been identified. Various noble families began building estates here. The town hall (pictured left) was built in 1400 for the Newfoundland Correale family who lived there from 1458 to 1501. Then it was taken over by the Grimaldi Gerace family until 1806. The book "Opera pastorale di Annibale d'Afflitto" by Antonio Denis tells of the 1595 visits by priests, clerics and deacons to the abbey. On August 27, 1663 they began building the Church of St Joseph and the first stone was blessed on March 12, 1667. The church was magnificent, but all this splendor ended a century later. The earthquake of February 5, 1783 left Molochio in rubble, destroying every building including the five churches in the town. In 1789 Molochio got its new church built by the Cassa Sacra Parish of Catanzaro, where it was previously built by Msgr. Palermo 118 years earlier. In 1811 Molochio became a municipality. During this time the population grew, so a new church was needed. On May 11, 1847, the priest blessed the first stone of the new church under the title of St. Maria de Merula. On September 17, 1853 the church structure was completed, but it was without an altar or final plaster. Services were held in the unfinished building as work continued. It was completed on June 10, 1860. Unfortunately, the earthquake of 1908 left the molochiesi once again deprived of their parish church. It remained closed for worship until 1916 when the church was looted. It was restored and began holding services again on Christmas Eve of 1921. The Civic Tower, called by many the symbol of Molochio was built after this earthquake. This small town's historical records date back to the years 1275 - 1279 when the Abbey of Santa Maria de Merula of Molochio is believed to have been built here, but the precise location has never been identified. Various noble families began building estates here. The town hall (pictured left) was built in 1400 for the Newfoundland Correale family who lived there from 1458 to 1501. Then it was taken over by the Grimaldi Gerace family until 1806. The book "Opera pastorale di Annibale d'Afflitto" by Antonio Denis tells of the 1595 visits by priests, clerics and deacons to the abbey. On August 27, 1663 they began building the Church of St Joseph and the first stone was blessed on March 12, 1667. The church was magnificent, but all this splendor ended a century later. The earthquake of February 5, 1783 left Molochio in rubble, destroying every building including the five churches in the town. In 1789 Molochio got its new church built by the Cassa Sacra Parish of Catanzaro, where it was previously built by Msgr. Palermo 118 years earlier. In 1811 Molochio became a municipality. During this time the population grew, so a new church was needed. On May 11, 1847, the priest blessed the first stone of the new church under the title of St. Maria de Merula. On September 17, 1853 the church structure was completed, but it was without an altar or final plaster. Services were held in the unfinished building as work continued. It was completed on June 10, 1860. Unfortunately, the earthquake of 1908 left the molochiesi once again deprived of their parish church. It remained closed for worship until 1916 when the church was looted. It was restored and began holding services again on Christmas Eve of 1921. The Civic Tower, called by many the symbol of Molochio was built after this earthquake.

The churches and other religious buildings in the town are: The churches and other religious buildings in the town are:

- Church of Santa Maria de Merola (pictured right), now located in Piazza Vittorio Emanuele III. The interior holds a painting created in the 15-16th centuries by an unknown artist, that is considered miraculous by molochiesi. This miniature of the Entombment of Christ is linked to a ritual that happens every year: at the end of the evening celebrations on Christmas and Easter, the faithful kiss the picture lovingly.

- Church of San Vito, built in the seventeenth century by Don Giuseppe Palermo includes statues of St. Rocco, the Madonna and St. Vito.

- Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes. The first shrine in Italy to be dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes was built here in 1901 at the Marian Convent. Behind the altar is kept the wooden statue of the Madonna of Lourdes sculpted in Paris in the late nineteenth century and donated by Countess Maria Probeck.

- Church of St. Joseph, who is their patron saint, was commissioned by Bishop Palermo and built in the Byzantine style on the ruins of the abbey.

Festivals are family affairs in Molochio, with the celebration of religious holidays and civil celebrations on the streets with music and fireworks. Typical of these rites is one called a Tocca (to touch) that takes place on Easter Sunday before the worship celebration. The parish priest accompanied by a young child travels around the village with a noisy instrument banging (touching) on it to announce the Resurrection of Christ.

The ritual of Virgineij (pictures of 2004 on right) happens the week before the feast of St Joseph, which is a time concerned with the neediest children in the village. This ritual has deep roots in the community, formerly large and important families hosted the less fortunate folk, to fulfill a vow made to the patron saint St. Joseph. It was a feast for the poorest who often had no food, who had only the task of bringing with them the dish and a spoon. It is similar to a country fair for it invites the entire citizenry to dine outdoors on food that have roots in their culture: pasta and chickpeas, pancakes with salt cod and sardines, bread, cheese and an apple, as well the inevitable glass of good wine. The most happy at this banquet were the children of the country who were welcomed with love and received special attention by the hosts and were given the name Virgineji. Today, even adults are offered this lunch for grace received or for "having made a vow." It all begins after the conclusion of the novena in honor of St. Joseph. The day is also cheered by the sound of the now famous Tamburinari (drummers) that perform around the tables, increasing joy and happiness. After the meal the people process through the streets. At the end of the procession the festivities of are closed in honor of their patron, St. Joseph. The ritual of Virgineij (pictures of 2004 on right) happens the week before the feast of St Joseph, which is a time concerned with the neediest children in the village. This ritual has deep roots in the community, formerly large and important families hosted the less fortunate folk, to fulfill a vow made to the patron saint St. Joseph. It was a feast for the poorest who often had no food, who had only the task of bringing with them the dish and a spoon. It is similar to a country fair for it invites the entire citizenry to dine outdoors on food that have roots in their culture: pasta and chickpeas, pancakes with salt cod and sardines, bread, cheese and an apple, as well the inevitable glass of good wine. The most happy at this banquet were the children of the country who were welcomed with love and received special attention by the hosts and were given the name Virgineji. Today, even adults are offered this lunch for grace received or for "having made a vow." It all begins after the conclusion of the novena in honor of St. Joseph. The day is also cheered by the sound of the now famous Tamburinari (drummers) that perform around the tables, increasing joy and happiness. After the meal the people process through the streets. At the end of the procession the festivities of are closed in honor of their patron, St. Joseph. |

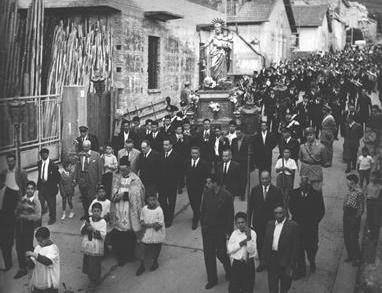

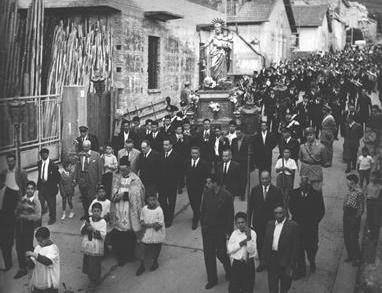

1960 St Joseph Procession |

|

| ~< Back to Top >~ |

Schools and Education today in Molochio is very different from the past. The old classroom had a wooden floor, two-seater benches with the teacher's chair on a platform. Each morning coals were heated and then brought into the classrooms in containers. The subjects taught were limited, the elementary school age children learned to read, write and count. There were many lessons that were held outdoors, especially in rural schools. In some areas a child could go up to the third grade with children of different ages. Nature was considered a book to read and study. The material used by the students was lacking: cardboard folders were a luxury for a few; only two books were provided; the students had little in the way of colors, older children used a pen dipped in ink and younger ones used ballpoint pens. There wasn't any recreation for the students. The school though materially poor, was spiritually rich: the teacher was not only the one who imparted knowledge, but he also instilled values and was an inspiration not only for his students but also for families and for all the community within which he held a unique role. Typically the teacher of an elementary school lived alone in the village. Very few students went off to higher education and many left school because there was so much poverty and they could not afford the many expenses for further study. Pictured left is the Elementary School in the summer of 1962. Schools and Education today in Molochio is very different from the past. The old classroom had a wooden floor, two-seater benches with the teacher's chair on a platform. Each morning coals were heated and then brought into the classrooms in containers. The subjects taught were limited, the elementary school age children learned to read, write and count. There were many lessons that were held outdoors, especially in rural schools. In some areas a child could go up to the third grade with children of different ages. Nature was considered a book to read and study. The material used by the students was lacking: cardboard folders were a luxury for a few; only two books were provided; the students had little in the way of colors, older children used a pen dipped in ink and younger ones used ballpoint pens. There wasn't any recreation for the students. The school though materially poor, was spiritually rich: the teacher was not only the one who imparted knowledge, but he also instilled values and was an inspiration not only for his students but also for families and for all the community within which he held a unique role. Typically the teacher of an elementary school lived alone in the village. Very few students went off to higher education and many left school because there was so much poverty and they could not afford the many expenses for further study. Pictured left is the Elementary School in the summer of 1962.

|

The people of the past rarely traveled away from home and only at certain times of year to go to work in the mountains; to go to the festivities, which take place in neighboring villages; or to visit a dying relative. This was because transportation was scarce, in fact they would travel using carts and few possessions, leaving much behind to others. More items could be taken by mule, but that was more expensive. Fifty years ago, the bicycle was little known and little used. Those that had one, found out how uncomfortable it was to use on the roads, then full of gravel and pebbles. Carts were also unreliable, because you could lose a wheel in the street or your mule could show signs of fatigue and stop moving. These means of transportation, of course, did not pollute and did not cause serious accidents such as today. The people of the past rarely traveled away from home and only at certain times of year to go to work in the mountains; to go to the festivities, which take place in neighboring villages; or to visit a dying relative. This was because transportation was scarce, in fact they would travel using carts and few possessions, leaving much behind to others. More items could be taken by mule, but that was more expensive. Fifty years ago, the bicycle was little known and little used. Those that had one, found out how uncomfortable it was to use on the roads, then full of gravel and pebbles. Carts were also unreliable, because you could lose a wheel in the street or your mule could show signs of fatigue and stop moving. These means of transportation, of course, did not pollute and did not cause serious accidents such as today.

Because the traffic was very limited they did not feel the need to create rules of the road. Instead, along the road, there were points of reference, like a big tree, or a source where people could stop to rest, partly because many people would walk along narrow winding mule trails in single file. The first paved roads are seen in Molochio about 50 years ago, during the economic boom that affected all of Italy. It was at that time that construction began of the road to Reggio Calabria, which today can be reached in less than an hour. But the new paved roads were not lit, so traveling at night was not easy. Most preferred to travel by day. The first electric lighting was installed in the early 1950s, although in a limited way. Then the first cars were seen in the streets, much slower than today. It was not until the 1960s, that the automobile became a common means of transport, thus reducing also the cultural distances and opening the village to new horizons. Because the traffic was very limited they did not feel the need to create rules of the road. Instead, along the road, there were points of reference, like a big tree, or a source where people could stop to rest, partly because many people would walk along narrow winding mule trails in single file. The first paved roads are seen in Molochio about 50 years ago, during the economic boom that affected all of Italy. It was at that time that construction began of the road to Reggio Calabria, which today can be reached in less than an hour. But the new paved roads were not lit, so traveling at night was not easy. Most preferred to travel by day. The first electric lighting was installed in the early 1950s, although in a limited way. Then the first cars were seen in the streets, much slower than today. It was not until the 1960s, that the automobile became a common means of transport, thus reducing also the cultural distances and opening the village to new horizons.

|

At the time of our grandfathers, children started to work at an early age, from 10 -12 years of age. They worked tirelessly from morning to evening and sometimes at night and the pay was rather poor. Such was the life: physical labor, low pay and almost no health care, but everyone did everything they could to earn money for their family. The would sometimes sing at work to ward off the fatigue. They worked in the countryside and mountains and at noon they ate what was put in the morning fiddle. The fiddle consisted of a handkerchief which held the food all day: some bread, olives, dried, boiled potatoes, beans or other produce. Cooked food was placed in containers called camels. The men tied the fiddle to a piece of wood and carried it on their shoulder, the women placed it on their head and walked briskly. Workplace food was consumed close to the trunks of trees on the ground or on logs cut into a seat. Some were lucky enough to work in the country where there was a cook house where they cooked what the land offered. The food was placed in large earthenware containers, called limbo. The dishes were common and all ate with wooden sticks. In the evening, after a long and laborious work day, men and women dedicated themselves to other activities: to the cleanliness and the household management; to the linen; to the cultivation of the actual grounds, for those who had the luck to possess it; and to the sewing and embroidery. Not having electricity, everything was done using candles or oil lanterns. Work was scarce and often not enough to sustain families, once very numerous. Some were forced to emigrate to distant lands, such as America, Australia or France. Sometimes they left and never came back to their own land. (Pictured above: Olive Grove with Orange Trees.) At the time of our grandfathers, children started to work at an early age, from 10 -12 years of age. They worked tirelessly from morning to evening and sometimes at night and the pay was rather poor. Such was the life: physical labor, low pay and almost no health care, but everyone did everything they could to earn money for their family. The would sometimes sing at work to ward off the fatigue. They worked in the countryside and mountains and at noon they ate what was put in the morning fiddle. The fiddle consisted of a handkerchief which held the food all day: some bread, olives, dried, boiled potatoes, beans or other produce. Cooked food was placed in containers called camels. The men tied the fiddle to a piece of wood and carried it on their shoulder, the women placed it on their head and walked briskly. Workplace food was consumed close to the trunks of trees on the ground or on logs cut into a seat. Some were lucky enough to work in the country where there was a cook house where they cooked what the land offered. The food was placed in large earthenware containers, called limbo. The dishes were common and all ate with wooden sticks. In the evening, after a long and laborious work day, men and women dedicated themselves to other activities: to the cleanliness and the household management; to the linen; to the cultivation of the actual grounds, for those who had the luck to possess it; and to the sewing and embroidery. Not having electricity, everything was done using candles or oil lanterns. Work was scarce and often not enough to sustain families, once very numerous. Some were forced to emigrate to distant lands, such as America, Australia or France. Sometimes they left and never came back to their own land. (Pictured above: Olive Grove with Orange Trees.)

Once the boys were directed by their parents from an early age to learn a trade, they had the opportunity to build the foundations for a solid future in a time of great insecurity and few certainties. This sort of inheritance, therefore, left little room to doubt the abilities of the individual but it was undoubtedly the surest way to guarantee a tomorrow, and for this reason, was taken without much hesitation and accepted with deep humility and dedication, as a true store of wealth, an art handed down. Few had the opportunity to undertake higher studies, so many had no choice but to follow in the footsteps of the family occupation or find fortune abroad. Many jobs that once allowed families to live decently even in simplicity, are now missing or are now practiced by very few: the shoemaker, the tailor, the coal, the plumber, the carpenter, the auctioneer, the factor, the guardian, the carpenter, the cofanaro, the washerwoman, the carrier, and the steward. Once the boys were directed by their parents from an early age to learn a trade, they had the opportunity to build the foundations for a solid future in a time of great insecurity and few certainties. This sort of inheritance, therefore, left little room to doubt the abilities of the individual but it was undoubtedly the surest way to guarantee a tomorrow, and for this reason, was taken without much hesitation and accepted with deep humility and dedication, as a true store of wealth, an art handed down. Few had the opportunity to undertake higher studies, so many had no choice but to follow in the footsteps of the family occupation or find fortune abroad. Many jobs that once allowed families to live decently even in simplicity, are now missing or are now practiced by very few: the shoemaker, the tailor, the coal, the plumber, the carpenter, the auctioneer, the factor, the guardian, the carpenter, the cofanaro, the washerwoman, the carrier, and the steward.

The Cristarella name is listed under the following occupations: a tailor of men's clothing; a joiner who was also listed as producing handicrafts, who bought and built the tops and small chairs for children; a plumber who also worked with tin and sheet metal; and a famous shoemaker. This is very interesting being that Concetto and his father Bruno are both listed as a shoemakers on their passenger lists.

|

| ~< Back to Top >~ |

Molochio from above |

|

Years ago, Molochio families were very large and mostly lived in confined houses with a lack of essential facilities. They lived off the earth. Therefore, the day began at dawn when they went to work on the land before going to their jobs. This situation led to an increase in the birth rate, for many children meant many workers. Fruit and vegetables were, therefore, the main food consumed, while some of these products were intended for sale. The breeding of animals for food was common. The slaughter of a pig was a real event for the family. Pork was the main meat, especially in summer. This simple way of life formed their society as children were married at a very young age, forming their own families. This was also due to the short life span, in most cases folks did not reach their 65th year.

Engagements and weddings had to follow strict rules involving a series of agreements between families. Men and women could not engage freely, indeed, they could not even talk to each other. Most marriages were decided by families and boyfriends could express their love only after approval of the parents.

Where a boy fell in love with a girl seeing her in church or at least from a distance, he had to turn first to his and then her father, to ask for her hand.

The boy in love would place a block/stump in front of the girl's house. If it was welcomed, the marriage was feasible, otherwise he was to give up.

Serenades mostly took place outside the window of his beloved who he wished to marry. He would play concertinas, accordions, guitars and drums and sing. When the engagement was denied, boys could dare to kiss the girl outside the church, compromising her, so her parents had to consent to avoid a scandal. The couple could not go out alone, they had to be accompanied by someone in the family. The engagement could not break easily because it was a disgrace to the bride, once engaged, they had to get married. The average age ranged from 16 to 18 years old. The bride's parents had to provide the dowry that consisted of linen in quantity and quality, depending on the economic situation. Parents of the groom had to buy the furniture and decorate the house. The costs of the marriage was paid by both families. The parents of the groom purchased the wedding attire: the bride's dress has to be long and white and the groom's garment was black with a white shirt. Poor families had to settle for a classic cocktail outfits. Weddings were celebrated in the home or in a hall adjacent to the cinema. They could last for days dancing the tarantella. Engagements and weddings had to follow strict rules involving a series of agreements between families. Men and women could not engage freely, indeed, they could not even talk to each other. Most marriages were decided by families and boyfriends could express their love only after approval of the parents.

Where a boy fell in love with a girl seeing her in church or at least from a distance, he had to turn first to his and then her father, to ask for her hand.

The boy in love would place a block/stump in front of the girl's house. If it was welcomed, the marriage was feasible, otherwise he was to give up.

Serenades mostly took place outside the window of his beloved who he wished to marry. He would play concertinas, accordions, guitars and drums and sing. When the engagement was denied, boys could dare to kiss the girl outside the church, compromising her, so her parents had to consent to avoid a scandal. The couple could not go out alone, they had to be accompanied by someone in the family. The engagement could not break easily because it was a disgrace to the bride, once engaged, they had to get married. The average age ranged from 16 to 18 years old. The bride's parents had to provide the dowry that consisted of linen in quantity and quality, depending on the economic situation. Parents of the groom had to buy the furniture and decorate the house. The costs of the marriage was paid by both families. The parents of the groom purchased the wedding attire: the bride's dress has to be long and white and the groom's garment was black with a white shirt. Poor families had to settle for a classic cocktail outfits. Weddings were celebrated in the home or in a hall adjacent to the cinema. They could last for days dancing the tarantella.

Generally people had little leisure time at their disposal, however, the men, when they could, were devoted to hunting and brought home thrushes, sparrows, and fox. They met also with friends to play cards and drink wine. Folks would meet in the square and went to visit friends, especially when the weather permitted. Non working days were Christmas, Easter, St. Joseph's Day and weddings when families reunited and enjoyed a meal with meat. Money was carefully guarded and never wasted, contrary to what happens in some circumstances today. They settled for fewer things, but lived serenely and with simplicity. The evening was around the campfire, listening to grandparents telling their stories, riddles, tongue twisters and praying the Rosary. They rarely went to the cinema and women were more likely prohibited.

|

| ~< Back to Top >~ |

The Waterfalls |

|

|

Palata |

Mundu |

|

|

Galasia |

Schioppo i middio |

|

|

|

Bernard Camillo Fountain |

European Space Agency image |

| ~< Back to Top >~ ~< Back to the Family Page >~ |

The inhabitants are called Molochiesi and there are about 1,000 families in 1,600 homes. As of December 31, 2004, it had a population of 2,700 which has been steadily decreasing over the years. The town is now divided into three areas: the old town where there are the remains of interesting noble palaces with beautiful granite portals; the area that developed between the two World Wars; and the modern town.

The inhabitants are called Molochiesi and there are about 1,000 families in 1,600 homes. As of December 31, 2004, it had a population of 2,700 which has been steadily decreasing over the years. The town is now divided into three areas: the old town where there are the remains of interesting noble palaces with beautiful granite portals; the area that developed between the two World Wars; and the modern town.  This small town's historical records date back to the years 1275 - 1279 when the Abbey of Santa Maria de Merula of Molochio is believed to have been built here, but the precise location has never been identified. Various noble families began building estates here. The town hall (pictured left) was built in 1400 for the Newfoundland Correale family who lived there from 1458 to 1501. Then it was taken over by the Grimaldi Gerace family until 1806. The book "Opera pastorale di Annibale d'Afflitto" by Antonio Denis tells of the 1595 visits by priests, clerics and deacons to the abbey. On August 27, 1663 they began building the Church of St Joseph and the first stone was blessed on March 12, 1667. The church was magnificent, but all this splendor ended a century later. The earthquake of February 5, 1783 left Molochio in rubble, destroying every building including the five churches in the town. In 1789 Molochio got its new church built by the Cassa Sacra Parish of Catanzaro, where it was previously built by Msgr. Palermo 118 years earlier. In 1811 Molochio became a municipality. During this time the population grew, so a new church was needed. On May 11, 1847, the priest blessed the first stone of the new church under the title of St. Maria de Merula. On September 17, 1853 the church structure was completed, but it was without an altar or final plaster. Services were held in the unfinished building as work continued. It was completed on June 10, 1860. Unfortunately, the earthquake of 1908 left the molochiesi once again deprived of their parish church. It remained closed for worship until 1916 when the church was looted. It was restored and began holding services again on Christmas Eve of 1921. The Civic Tower, called by many the symbol of Molochio was built after this earthquake.

This small town's historical records date back to the years 1275 - 1279 when the Abbey of Santa Maria de Merula of Molochio is believed to have been built here, but the precise location has never been identified. Various noble families began building estates here. The town hall (pictured left) was built in 1400 for the Newfoundland Correale family who lived there from 1458 to 1501. Then it was taken over by the Grimaldi Gerace family until 1806. The book "Opera pastorale di Annibale d'Afflitto" by Antonio Denis tells of the 1595 visits by priests, clerics and deacons to the abbey. On August 27, 1663 they began building the Church of St Joseph and the first stone was blessed on March 12, 1667. The church was magnificent, but all this splendor ended a century later. The earthquake of February 5, 1783 left Molochio in rubble, destroying every building including the five churches in the town. In 1789 Molochio got its new church built by the Cassa Sacra Parish of Catanzaro, where it was previously built by Msgr. Palermo 118 years earlier. In 1811 Molochio became a municipality. During this time the population grew, so a new church was needed. On May 11, 1847, the priest blessed the first stone of the new church under the title of St. Maria de Merula. On September 17, 1853 the church structure was completed, but it was without an altar or final plaster. Services were held in the unfinished building as work continued. It was completed on June 10, 1860. Unfortunately, the earthquake of 1908 left the molochiesi once again deprived of their parish church. It remained closed for worship until 1916 when the church was looted. It was restored and began holding services again on Christmas Eve of 1921. The Civic Tower, called by many the symbol of Molochio was built after this earthquake.

The churches and other religious buildings in the town are:

The churches and other religious buildings in the town are:

The ritual of Virgineij (pictures of 2004 on right) happens the week before the feast of St Joseph, which is a time concerned with the neediest children in the village. This ritual has deep roots in the community, formerly large and important families hosted the less fortunate folk, to fulfill a vow made to the patron saint St. Joseph. It was a feast for the poorest who often had no food, who had only the task of bringing with them the dish and a spoon. It is similar to a country fair for it invites the entire citizenry to dine outdoors on food that have roots in their culture: pasta and chickpeas, pancakes with salt cod and sardines, bread, cheese and an apple, as well the inevitable glass of good wine. The most happy at this banquet were the children of the country who were welcomed with love and received special attention by the hosts and were given the name Virgineji. Today, even adults are offered this lunch for grace received or for "having made a vow." It all begins after the conclusion of the novena in honor of St. Joseph. The day is also cheered by the sound of the now famous Tamburinari (drummers) that perform around the tables, increasing joy and happiness. After the meal the people process through the streets. At the end of the procession the festivities of are closed in honor of their patron, St. Joseph.

The ritual of Virgineij (pictures of 2004 on right) happens the week before the feast of St Joseph, which is a time concerned with the neediest children in the village. This ritual has deep roots in the community, formerly large and important families hosted the less fortunate folk, to fulfill a vow made to the patron saint St. Joseph. It was a feast for the poorest who often had no food, who had only the task of bringing with them the dish and a spoon. It is similar to a country fair for it invites the entire citizenry to dine outdoors on food that have roots in their culture: pasta and chickpeas, pancakes with salt cod and sardines, bread, cheese and an apple, as well the inevitable glass of good wine. The most happy at this banquet were the children of the country who were welcomed with love and received special attention by the hosts and were given the name Virgineji. Today, even adults are offered this lunch for grace received or for "having made a vow." It all begins after the conclusion of the novena in honor of St. Joseph. The day is also cheered by the sound of the now famous Tamburinari (drummers) that perform around the tables, increasing joy and happiness. After the meal the people process through the streets. At the end of the procession the festivities of are closed in honor of their patron, St. Joseph.

Schools and Education today in Molochio is very different from the past. The old classroom had a wooden floor, two-seater benches with the teacher's chair on a platform. Each morning coals were heated and then brought into the classrooms in containers. The subjects taught were limited, the elementary school age children learned to read, write and count. There were many lessons that were held outdoors, especially in rural schools. In some areas a child could go up to the third grade with children of different ages. Nature was considered a book to read and study. The material used by the students was lacking: cardboard folders were a luxury for a few; only two books were provided; the students had little in the way of colors, older children used a pen dipped in ink and younger ones used ballpoint pens. There wasn't any recreation for the students. The school though materially poor, was spiritually rich: the teacher was not only the one who imparted knowledge, but he also instilled values and was an inspiration not only for his students but also for families and for all the community within which he held a unique role. Typically the teacher of an elementary school lived alone in the village. Very few students went off to higher education and many left school because there was so much poverty and they could not afford the many expenses for further study. Pictured left is the Elementary School in the summer of 1962.

Schools and Education today in Molochio is very different from the past. The old classroom had a wooden floor, two-seater benches with the teacher's chair on a platform. Each morning coals were heated and then brought into the classrooms in containers. The subjects taught were limited, the elementary school age children learned to read, write and count. There were many lessons that were held outdoors, especially in rural schools. In some areas a child could go up to the third grade with children of different ages. Nature was considered a book to read and study. The material used by the students was lacking: cardboard folders were a luxury for a few; only two books were provided; the students had little in the way of colors, older children used a pen dipped in ink and younger ones used ballpoint pens. There wasn't any recreation for the students. The school though materially poor, was spiritually rich: the teacher was not only the one who imparted knowledge, but he also instilled values and was an inspiration not only for his students but also for families and for all the community within which he held a unique role. Typically the teacher of an elementary school lived alone in the village. Very few students went off to higher education and many left school because there was so much poverty and they could not afford the many expenses for further study. Pictured left is the Elementary School in the summer of 1962. The people of the past rarely traveled away from home and only at certain times of year to go to work in the mountains; to go to the festivities, which take place in neighboring villages; or to visit a dying relative. This was because transportation was scarce, in fact they would travel using carts and few possessions, leaving much behind to others. More items could be taken by mule, but that was more expensive. Fifty years ago, the bicycle was little known and little used. Those that had one, found out how uncomfortable it was to use on the roads, then full of gravel and pebbles. Carts were also unreliable, because you could lose a wheel in the street or your mule could show signs of fatigue and stop moving. These means of transportation, of course, did not pollute and did not cause serious accidents such as today.

The people of the past rarely traveled away from home and only at certain times of year to go to work in the mountains; to go to the festivities, which take place in neighboring villages; or to visit a dying relative. This was because transportation was scarce, in fact they would travel using carts and few possessions, leaving much behind to others. More items could be taken by mule, but that was more expensive. Fifty years ago, the bicycle was little known and little used. Those that had one, found out how uncomfortable it was to use on the roads, then full of gravel and pebbles. Carts were also unreliable, because you could lose a wheel in the street or your mule could show signs of fatigue and stop moving. These means of transportation, of course, did not pollute and did not cause serious accidents such as today.  Because the traffic was very limited they did not feel the need to create rules of the road. Instead, along the road, there were points of reference, like a big tree, or a source where people could stop to rest, partly because many people would walk along narrow winding mule trails in single file. The first paved roads are seen in Molochio about 50 years ago, during the economic boom that affected all of Italy. It was at that time that construction began of the road to Reggio Calabria, which today can be reached in less than an hour. But the new paved roads were not lit, so traveling at night was not easy. Most preferred to travel by day. The first electric lighting was installed in the early 1950s, although in a limited way. Then the first cars were seen in the streets, much slower than today. It was not until the 1960s, that the automobile became a common means of transport, thus reducing also the cultural distances and opening the village to new horizons.

Because the traffic was very limited they did not feel the need to create rules of the road. Instead, along the road, there were points of reference, like a big tree, or a source where people could stop to rest, partly because many people would walk along narrow winding mule trails in single file. The first paved roads are seen in Molochio about 50 years ago, during the economic boom that affected all of Italy. It was at that time that construction began of the road to Reggio Calabria, which today can be reached in less than an hour. But the new paved roads were not lit, so traveling at night was not easy. Most preferred to travel by day. The first electric lighting was installed in the early 1950s, although in a limited way. Then the first cars were seen in the streets, much slower than today. It was not until the 1960s, that the automobile became a common means of transport, thus reducing also the cultural distances and opening the village to new horizons. At the time of our grandfathers, children started to work at an early age, from 10 -12 years of age. They worked tirelessly from morning to evening and sometimes at night and the pay was rather poor. Such was the life: physical labor, low pay and almost no health care, but everyone did everything they could to earn money for their family. The would sometimes sing at work to ward off the fatigue. They worked in the countryside and mountains and at noon they ate what was put in the morning fiddle. The fiddle consisted of a handkerchief which held the food all day: some bread, olives, dried, boiled potatoes, beans or other produce. Cooked food was placed in containers called camels. The men tied the fiddle to a piece of wood and carried it on their shoulder, the women placed it on their head and walked briskly. Workplace food was consumed close to the trunks of trees on the ground or on logs cut into a seat. Some were lucky enough to work in the country where there was a cook house where they cooked what the land offered. The food was placed in large earthenware containers, called limbo. The dishes were common and all ate with wooden sticks. In the evening, after a long and laborious work day, men and women dedicated themselves to other activities: to the cleanliness and the household management; to the linen; to the cultivation of the actual grounds, for those who had the luck to possess it; and to the sewing and embroidery. Not having electricity, everything was done using candles or oil lanterns. Work was scarce and often not enough to sustain families, once very numerous. Some were forced to emigrate to distant lands, such as America, Australia or France. Sometimes they left and never came back to their own land. (Pictured above:

At the time of our grandfathers, children started to work at an early age, from 10 -12 years of age. They worked tirelessly from morning to evening and sometimes at night and the pay was rather poor. Such was the life: physical labor, low pay and almost no health care, but everyone did everything they could to earn money for their family. The would sometimes sing at work to ward off the fatigue. They worked in the countryside and mountains and at noon they ate what was put in the morning fiddle. The fiddle consisted of a handkerchief which held the food all day: some bread, olives, dried, boiled potatoes, beans or other produce. Cooked food was placed in containers called camels. The men tied the fiddle to a piece of wood and carried it on their shoulder, the women placed it on their head and walked briskly. Workplace food was consumed close to the trunks of trees on the ground or on logs cut into a seat. Some were lucky enough to work in the country where there was a cook house where they cooked what the land offered. The food was placed in large earthenware containers, called limbo. The dishes were common and all ate with wooden sticks. In the evening, after a long and laborious work day, men and women dedicated themselves to other activities: to the cleanliness and the household management; to the linen; to the cultivation of the actual grounds, for those who had the luck to possess it; and to the sewing and embroidery. Not having electricity, everything was done using candles or oil lanterns. Work was scarce and often not enough to sustain families, once very numerous. Some were forced to emigrate to distant lands, such as America, Australia or France. Sometimes they left and never came back to their own land. (Pictured above: Once the boys were directed by their parents from an early age to learn a trade, they had the opportunity to build the foundations for a solid future in a time of great insecurity and few certainties. This sort of inheritance, therefore, left little room to doubt the abilities of the individual but it was undoubtedly the surest way to guarantee a tomorrow, and for this reason, was taken without much hesitation and accepted with deep humility and dedication, as a true store of wealth, an art handed down. Few had the opportunity to undertake higher studies, so many had no choice but to follow in the footsteps of the family occupation or find fortune abroad. Many jobs that once allowed families to live decently even in simplicity, are now missing or are now practiced by very few: the shoemaker, the tailor, the coal, the plumber, the carpenter, the auctioneer, the factor, the guardian, the carpenter, the cofanaro, the washerwoman, the carrier, and the steward.

Once the boys were directed by their parents from an early age to learn a trade, they had the opportunity to build the foundations for a solid future in a time of great insecurity and few certainties. This sort of inheritance, therefore, left little room to doubt the abilities of the individual but it was undoubtedly the surest way to guarantee a tomorrow, and for this reason, was taken without much hesitation and accepted with deep humility and dedication, as a true store of wealth, an art handed down. Few had the opportunity to undertake higher studies, so many had no choice but to follow in the footsteps of the family occupation or find fortune abroad. Many jobs that once allowed families to live decently even in simplicity, are now missing or are now practiced by very few: the shoemaker, the tailor, the coal, the plumber, the carpenter, the auctioneer, the factor, the guardian, the carpenter, the cofanaro, the washerwoman, the carrier, and the steward.

Engagements and weddings had to follow strict rules involving a series of agreements between families. Men and women could not engage freely, indeed, they could not even talk to each other. Most marriages were decided by families and boyfriends could express their love only after approval of the parents.

Where a boy fell in love with a girl seeing her in church or at least from a distance, he had to turn first to his and then her father, to ask for her hand.

The boy in love would place a block/stump in front of the girl's house. If it was welcomed, the marriage was feasible, otherwise he was to give up.

Serenades mostly took place outside the window of his beloved who he wished to marry. He would play concertinas, accordions, guitars and drums and sing. When the engagement was denied, boys could dare to kiss the girl outside the church, compromising her, so her parents had to consent to avoid a scandal. The couple could not go out alone, they had to be accompanied by someone in the family. The engagement could not break easily because it was a disgrace to the bride, once engaged, they had to get married. The average age ranged from 16 to 18 years old. The bride's parents had to provide the dowry that consisted of linen in quantity and quality, depending on the economic situation. Parents of the groom had to buy the furniture and decorate the house. The costs of the marriage was paid by both families. The parents of the groom purchased the wedding attire: the bride's dress has to be long and white and the groom's garment was black with a white shirt. Poor families had to settle for a classic cocktail outfits. Weddings were celebrated in the home or in a hall adjacent to the cinema. They could last for days dancing the tarantella.

Engagements and weddings had to follow strict rules involving a series of agreements between families. Men and women could not engage freely, indeed, they could not even talk to each other. Most marriages were decided by families and boyfriends could express their love only after approval of the parents.

Where a boy fell in love with a girl seeing her in church or at least from a distance, he had to turn first to his and then her father, to ask for her hand.

The boy in love would place a block/stump in front of the girl's house. If it was welcomed, the marriage was feasible, otherwise he was to give up.

Serenades mostly took place outside the window of his beloved who he wished to marry. He would play concertinas, accordions, guitars and drums and sing. When the engagement was denied, boys could dare to kiss the girl outside the church, compromising her, so her parents had to consent to avoid a scandal. The couple could not go out alone, they had to be accompanied by someone in the family. The engagement could not break easily because it was a disgrace to the bride, once engaged, they had to get married. The average age ranged from 16 to 18 years old. The bride's parents had to provide the dowry that consisted of linen in quantity and quality, depending on the economic situation. Parents of the groom had to buy the furniture and decorate the house. The costs of the marriage was paid by both families. The parents of the groom purchased the wedding attire: the bride's dress has to be long and white and the groom's garment was black with a white shirt. Poor families had to settle for a classic cocktail outfits. Weddings were celebrated in the home or in a hall adjacent to the cinema. They could last for days dancing the tarantella.